Following its weakest performance since the global financial crisis, the world economy is poised for a modest rebound this year– if everything goes just right.

Hanging over this lethargic recovery are two other trends that raise questions about the course of economic growth: the unprecedented runup in debt worldwide, and the prolonged deceleration of productivity growth, which needs to pick up to bolster standards of living and poverty eradication.

Global growth is set to rise by 2.5% this year, a small uptick from 2.4% in 2019, as trade and investment gradually recover, the World Bank’s semi-annual Global Economic Prospects forecasts. Advanced economies are expected to slow as a group to 1.4% from 1.6%, mainly reflecting lingering weakness in manufacturing.

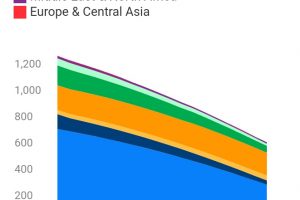

Emerging market and developing economies will see growth accelerate to 4.1% from 3.5% last year. However, the pickup is anticipated to come largely from a small number of large emerging economies shaking off economic doldrums or stabilizing after recession or turbulence. For many other economies, growth is on track to decelerate as exports and investment remain weak.

A worrying aspect of the sluggish growth trend is that even if the recovery in emerging and developing economy growth takes place as expected, per capita growth will remain below long-term averages and will advance at a pace too slow to meet poverty eradication goals. Income growth would in fact be slowest in Sub-Saharan Africa – the region where 56 percent of the world’s poor live.

And even this modest rally could be disrupted by any number of threats. Trade disputes could re-escalate. A sharper-than-expected growth slowdown in major economies such as China, the United States, or the Euro Area would similarly reverberate widely. A resurgence of financial stress in large emerging markets, as was experienced in Argentina and Turkey in 2018, an escalation of geopolitical tensions, or a series of extreme weather events could all have adverse effects on economic activity around the world.

Debt Wave- One feature overshadowing the outlook is the largest, fastest, and most broad-based wave of debt accumulation among emerging and developing economies in the last 50 years. Total debt among these economies climbed to about 170% of GDP in 2018 from 115% of GDP in 2010. Debt has also surged among low-income countries after a sharp drop over 2000-2010.

The current wave of debt differs from previous ones in that there has been an increase in the share of non-resident holdings of EMDE government debt, foreign currency-denominated private EMDE debt, and, for low-income countries, borrowing from financial markets and non-Paris Club bilateral creditors, raising concerns about debt transparency and debt collateralization.

Public borrowing can be beneficial and spur economic development, if used to finance growth- enhancing investments, such as in infrastructure, health care, and education. Debt accumulation can also be appropriate in economic downturns as a way to stabilize economic activity.

However, the three previous waves of debt accumulation have ended badly – sovereign defaults in the early 1980s; financial crises in the late 1990s; the need for major debt relief in the 2000s; and the global financial crisis in 2008-2009. And while currently low interest rates mitigate some of the risks, high debt carries significant risks. It can leave countries to vulnerable to external shocks; it can limit the ability of governments to counter downturns with fiscal stimulus; and it can dampen longer-term growth by crowding out productivity-enhancing private investment.

This means that governments need to take steps to minimize risks associated with debt buildups. Sound debt management and debt transparency can keep a lid on borrowing costs, enhance debt sustainability, and reduce fiscal risks. Strong regulatory and supervisory regimes, good corporate governance, and common international standards can help contain risks, ensure that debt is used productively, and identify vulnerabilities early.

Productivity Slowdown

Yet another aspect of the disappointing pace of global growth is the broad-based slowdown in productivity growth over the last ten years. Growth in productivity – output per worker – is essential to raising living standards and achieving development goals.

An extensive look at productivity trends in this edition of Global Economic Prospects focuses on how the productivity slowdown has affected emerging and developing economies. Average output per worker in emerging and developing economies is less than one-fifth that of a worker in an advanced economy, and in low-income economies that figure drops to 2%.

Among emerging and developing economies, which have a history of productivity growth surges and setbacks, the slowdown from 6.6% in 2007 to a trough of 3.2% in 2015 has been the steepest, longest, and broadest on record. The slowdown is due to weaker investment and efficiency gains, dwindling gains from the reallocation of resources to more productive sectors, and slowing improvements in the key drivers of productivity, such as education and institutional quality.

How to rekindle productivity growth? The outlook for productivity remains challenging. Therefore, efforts are needed to stimulate private and public investment; upgrade workforce skills to boost firm productivity; help resources find the most productive sectors; reinvigorate technology adoption and innovation; and promote a growth-friendly macroeconomic and institutional environment.

Two other issues merit consideration in this edition of the outlook: adverse consequences of price controls and inflation prospects in LICs. While price controls are sometimes considered a useful tool to smooth price fluctuations for good and services such as energy and food, they can also dampen investment and growth, worsen poverty outcomes, and lead to heavier fiscal burdens. Replacing them with expanded and targeted social safety nets alongside the encouragement of competition and an effective regulatory environment, can be beneficial both to poverty eradication and to growth.

And while inflation has declined sharply among low-income countries over the last 25 years, keeping it low and stable cannot be taken for granted. Low inflation is associated with more stable output and employment, higher investment, and falling poverty rates. However, rising debt levels and fiscal pressures could put some economies at risk of disruptions that could send prices sharply higher. Strengthening central bank independence, making the monetary authority’s objectives clear, and cementing central bank credibility are essential to keep prices anchored.

While the global economic outlook for 2020 envisions a fragile upward path that could be upended, there is high degree of uncertainty around the forecast given unpredictability around trade and other policies. If policy-makers manage to mitigate tensions and clarify unsettled issues in a number of areas – they could prove the forecast wrong by sending growth higher than anticipated.

January 2020 Global Economic Prospects: Slow growth, policy challenges

Add Comment